People have liked psychic effects ever since magicians first began performing them, and in recent years the public has leaned even more to that branch of magic. When a magician discovers a thought which one person alone knows, which hasn't been whispered to someone else or even written down, it is particularly impressive. The effect I am about to describe appears to be something of a miracle to the spectators, especially to those who take part and have their minds read. Of course, it needs to be presented with showmanship, as do all other tricks, to be completely effective. Showmanship with a psychic effect means presenting the trick exactly as if you had the power you pretend. It should be performed in as quiet a manner as possible, without any flourishes and, seemingly, without any pretense. The performer is a scientist who has discovered something greatly in advance of the knowledge of the rest of the world--he does not boast about it, nor does he rant about it. He merely, and quietly, proves it.

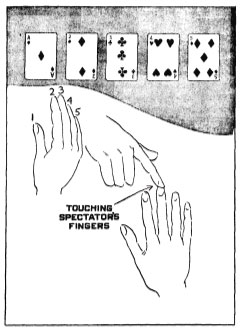

This is the effect of the trick. The performer removes five cards from a pack. The cards are the ace, deuce, trey, four, and five spot of any suits. It makes no difference whether they are of different suits or all of one suit. The cards are placed on a table in a row and in sequence. While the performer turns away, a person is asked to look at the cards and choose one, and only one, mentally. Then the magician turns to him and instructs him to think that his thumb represents the ace, his index finger the deuce, his middle finger the trey, and so on. Above all he is to concentrate on the card he has mentally selected by keeping his thoughts firmly on the finger which represents it. When the spectator thoroughly understands what he is to do and announces that he is ready, he is told to hold up his hand, with his fingers apart. With the tip of his index finger the performer lightly touches the tips of each of the spectator's fingers as he says, "Ace, deuce, trey, four, five." Then without saying anything else, or doing anything more, the magician turns to the table and picks up from the row of cards the very card of which the spectator is thinking.

The secret is very simple, the clue being given, quite unconsciously, by the spectator himself. But perhaps it would be best to explain the routine in order.

After the performer removes the five cards from the deck, he places them face up on the table running from left to right--at the extreme left is the ace, to the right of it the deuce, again to the right the trey, and so on. When I speak of left and right I mean the spectator's left and right. The cards are put in this order because the spectator is asked later to raise his right hand, palm toward the magician and in that position the thumb is towards the left and the fifth, or little finger, toward the right. It will be recalled that the thumb represents the ace and the little finger represents the five. As the cards are put on the table, they run in the same direction as the spectator thinks of his lingers. This is a minor point but one which makes a great deal of difference to the success of the trick, for it eliminates much confusion in getting the spectator to follow instructions.

After the performer removes the five cards from the deck, he places them face up on the table running from left to right--at the extreme left is the ace, to the right of it the deuce, again to the right the trey, and so on. When I speak of left and right I mean the spectator's left and right. The cards are put in this order because the spectator is asked later to raise his right hand, palm toward the magician and in that position the thumb is towards the left and the fifth, or little finger, toward the right. It will be recalled that the thumb represents the ace and the little finger represents the five. As the cards are put on the table, they run in the same direction as the spectator thinks of his lingers. This is a minor point but one which makes a great deal of difference to the success of the trick, for it eliminates much confusion in getting the spectator to follow instructions.

When the trick has reached the point where the spectator has his hand raised, seemingly nothing has happened which would give the magician the least clue as to which card is being held in mind by the spectator. As the magician lightly touches the tips of the spectator's fingers with the tip of his index finger, it seems merely as if the magician were trying to concentrate. It is not his concentration which matters, but the concentration of the spectator. When a person thinks hard upon one finger he stiffens that finger without being aware of it himself. When the performer touches the person's fingers he will get the impression he wants, namely that one finger is stiffer than the others. The performer does not push the fingers back and forth, nor exert any pressure on them, for the lightest touch will give him his clue. He merely touches them, apparently as a reminder to the spectator.

Once the magician knows which finger is being thought of by the spectator, he knows which card has been selected. He does not name the card nor even immediately pick it up. He goes back to the table and runs his hand over the cards a time or two and perhaps names them over "Ace, deuce, trey, four, five." He then picks up the chosen card or, as I prefer doing, turns the chosen card face down and announces: "That is your card."

The trick may he repeated again and again, and I have never failed to pick the correct card in four out of five tests with any group. The trick is not one hundred per cent certain but the percentage of success is very high. The few failures merely seem to make more convincing to the spectators that they have been witnessing a true demonstration of mind reading.

The trick is particularly effective when shown to only a few people such as to a group of newspaper reporters. When properly presented they will forget the hand and fingers part of the feat and recall only that the magician was able to tell which cards they had mentally chosen. They are apt also to forget that they were limited in their choice and that they had but five cards from which to make their selection.

Of course, it is just as possible to write numbers on five pieces of paper instead of using cards. Anything at all may be used from which to make a selection as long as there is something to take their minds off their fingers.

Incidentally, it is not a trick for magicians, although I have performed it successfully for a number. It is a trick for laymen. Laymen are only interested in the effect and they don't care, when the effect is good, whether what they have seen is difficult or easy, whether a new sleight is used or whether the gimmick is silver plated. Any further explanation is unnecessary. I feel certain that if you try it a few times you will find it to be a trick you will like.

0 comments:

New comments are not allowed.